Paris suburb digs up playgrounds to make school more cool

- Lise KIENNEMANN

- Oct 31, 2023

- 4 min read

By Lise Kiennemann

CLAMART, France, Oct 24 (Sciences Po) - It is a playground that went back to school – old school, that is, with trees and grass and shade.

In one of the eleven primary schools of Clamart, a suburb in the southwest of Paris, the asphalt was replaced during the summer by wood shavings, which allow water to seep through and absorb less heat. The 4,000 square meters courtyard was also granted 36 new trees and dozens of additional shrubs, which increased by a third its shaded area.

“The goal is to make children aware of nature, but also to make these courtyards more heat-resilient,” François Le Got, deputy mayor in charge of sustainable development, said.

In France, the vast majority of playgrounds are coated in asphalt, which absorbs and stores solar radiation and leads to an increase in surface temperatures.

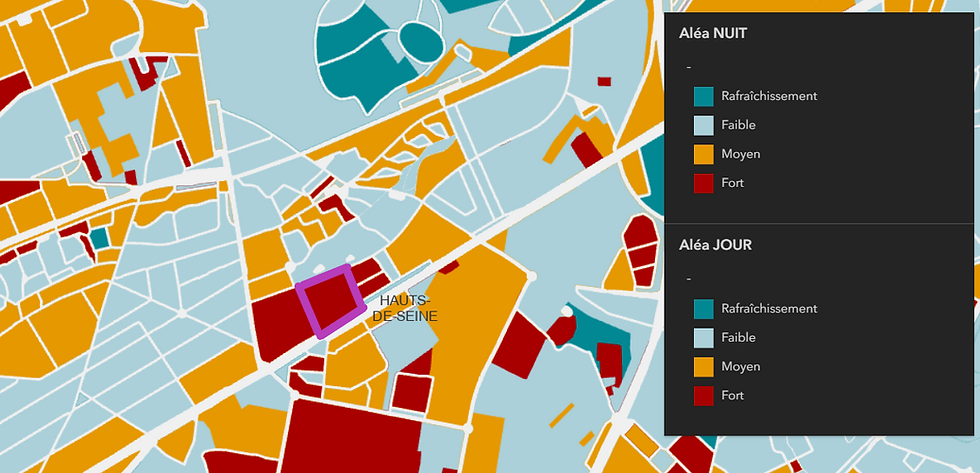

On a map published by the Institut de la Région de Paris - which classifies each urban block according to its urban morphology (including the presence of water or vegetation, the share of built-up areas or the thermal properties of materials) - the Léopold Senghor school is one of several areas to show up as “urban heat island”.

As climate change is making heatwaves more frequent and intense, this “urban heat island effect” is being amplified, forcing local councils to take action.

In Paris, less than ten kilometres away from Clamart, 130 of the 638 city public schools have already had their playground planted as a result of a resolution passed by the municipality in 2017, according to the website of the city hall. Other major French cities, like Toulouse, Lille or Lyon, are also starting to green their playgrounds.

This renovation work is costly. Converting Clamart courtyard from an expanse of asphalt into a park-like area cost 850,000 euros.

Vallée Sud (“South Valley”), an intercommunal structure which brings together Clamart and ten other Parisian suburbs, fully covered these costs, since the project is included in its “Territorial Climate Air Energy Plan” (PCAET, for “Plan Climat Air Énergie Territorial”). Since 2015, any intercommunal structure with more than 20,000 inhabitants has to design such a document, which aims at attenuating the effects of climate change by setting targets and an action programme.

On top of this initial cost, a greener courtyard brings new constraints, notably more maintenance.

But many cities consider that the benefits are worth the price, as the heatwave season is becoming increasingly longer. In 2023, France recorded its hottest month of September, and its second hottest month of June, behind 2003. According to Météo France, by 2100, France will experience 10 to 25 days of heatwave per year, compared to one day currently.

As finding space to green cities is a challenge in many cities, school playgrounds also appear to be one of the few places municipalities can have control over.

“Redesigning courtyards can reduce temperatures by 2 or 3 degrees,” Olivier Cantat, a climatologist and geographer at the University of Caen, said. "Trees do not only provide shade but also cool the air through evapotranspiration. By transpiring, the leaves reduce the heating of the street and increase the humidity of the air,” he added.

Choosing permeable soil, such as wood shavings, allows water to soak into the ground and then evaporate and cool the air.

“Wood shavings are also a good option because they prevent the ground from becoming muddy when it rains,” Le Got said.

But turning playgrounds into green oases does not only have environmental benefits. Advocates say it positively impacts child development and can help reconnect children with nature. A 2020 study published in Science advances found that greener play areas boost children’s immune systems too.

Clarmat's new playground has overall been well received by children and parents alike. Loïc Michel, president of the FCPE, one of the parents' associations of the school, and father of two children, said he is pleased about this "inspiring" initiative which protects children from heatwaves.

Despite these advantages, the municipality still had to deal with some resistance. "Some teachers have complained that children can ingest the wood shavings, and that these shavings get into the classrooms and attract insects with them," Le Got said.

But for Le Got, one of the project’s key benefits is precisely to learn to cohabit with nature."Such a courtyard allows urban children to be able to observe the rhythm of the seasons, and to learn to live with the environment and respect it," he said.

He said the town hall is trying to find solutions to address the problems that have been raised. For instance, small shovels have been added to the courtyard to allow the children to carry the wood shavings back to the areas where they belong.

The town’s efforts to tackle climate change are not confined to the Léopold Senghor school. This year, the playground of another school was replaced by lighter-colored asphalt that absorbs less heat.

As to the courtyards of the two recently built schools, they included large shaded areas from the beginning. "The days when we were building schools with asphalt courtyards are over," Le Got said.

Comments